by Viktorka Hlaváčková. Translated / edited by Jozef Antala

The second part of diary of Viktorka, Czech hiker who in summer 2017 traversed the Caucasus mountains. She started on 28.6 from Batumi and in next four months (few detours included) hiked all the way to the Caspian sea, sticking to the mountains as much as possible. First part of her diary can be found here

After saying farewell to Arash, I bypass Zhinvali reservoir and head north, towards the Gudamakari mountains. I meet only one jeep whose nice crew invites me for a picnic. Such is Georgia, people keep inviting me and I have to keep refusing them because otherwise, I wouldn´t get anywhere.

On the next day, I try to climb a hillside so steep that I spend the whole forenoon on all fours. But the scenery at the top of the ridge is beautiful - I am high on endorphins even though the grass is ungrazed, tall and full of thistles.

And as I rush towards the saddle where I plan to break a camp, gazing into the distance instead of watching my step, I stumble and fall. The ground is soft, but hip belt unbuckles and my camera case rolls down into the valley. I observe it and wait till it stops - running after it would be pointless, it is too fast. And so it rolls and rolls and bounces off the stones and I have a feeling that I´ve never seen something falling for such a long time. When it gets out of my sight. I drop my backpack, sit down and slide on my butt, realizing that even if I find it, I may not like what I see.

One hundred meter below, I find the camera case on the stones. But it's empty, I only spill out shattered lens. The camera itself lies nearby. It is battered but at least I can turn it on. At these moments, I still hope that once I will switch the lens, it will work. But I will cut it short - from this moment, it makes only black photos. And when I fall asleep in the evening, Cassiopea burns its W into my face and I watch out for some falling star so I can make a wish so I finally stop losing and destroying things.

On the next morning, I continue on the ridge and the mountains are so magnificent that trying to describe all that beauty by world would be blasphemous. When I descend in the afternoon to get to the closest road, I make a short break and get caught by 55-years old shepherd Dod. From spring till autumn, he herds his 1500 sheep and the remaining time spends as a security guy at the rugby stadium at Tbilisi. His "shack" is just an iron bed covered with a large sheet. I have a weakness for this kind of a primitive functional architecture so I have to admire his work. He invites me to spend a night there, while he would bivouac with the sheep. He even wants to kill mutton in the evening. But no can do, I need to hurry to Tbilisi to meet my husband. I only accept an invitation for cheese and coffee to make him happy and entertain him for a while. We cut the food with our 4-inch Opinels.

On the next day, I hitchhike to Tbilisi. Soon, I find an older camera guy - he sits on the pavement close to the Didibe station. He has an interesting assortment, the one I would hardly find in the local shops.

"I can sell you Nikon D90 with 18-55 lens for 500 lari"

, he offers after I tell him that I don't have much money.

"The guy nearby sells Nikon D90 with better lens also for 500 lari", I reply.

"OK, then 450 lari".

"No, 400 lari".

"Deal. And what about that broken camera? You don't need it anymore."

"I can give it to you, but the total price will be 350 lari".

The man hesitates for a moment, then nods.

"But I need also a charger and two spare batteries."

"Give me your charger and batteries, we will exchange them."

"And the price 350 stays?"

"Yes, 350 lari".

"OK, but I need also a polarization filter".

"It costs 30 lari, for 50, I will give you two."

"Give me one polarization and one UV filter".

One of his assistants brings a linen sack with at least fifty used filters, the man reaches inside and hands me what I need. I try out everything, pay and we shake hands as a sign of a good deal. I leave with a sentiment that shopping could be really fun. I only feel a bit sad because of the lost camera which served me so well.

I have no idea what word Gudamakari means in Georgian (if anything at all), but this lack of knowledge only adds to the mystery. The mountains reach from the Zhinvali reservoir to the north, towards the rocky three-thousanders rising at the horizon. This view evokes respect. Once you climb onto the first ridge, it´s immediately obvious that Gudamakari mountains are devoid of humans, forsaken and wild. That these are exactly that kind of mountains you can´t resist if you have at least some sense for the beauty and adventure.

To get to the place where I interrupted my trek, I hitch a ride with three grandpas. The driver asks me where do I go.

"Into the mountains. And then to Juta".

"You can get to Juta by road."

"I know, but I prefer mountains."

"But you can´t cross the mountains, it´s not possible"

"It is"

, I say confidently.

"We are locals, we know the place. What can you know?"

"You know it here but I look into the map and see that it´s possible".

Then he stops arguing. It is always possible, only sometimes it´s bigger suffering, I think, but also feel some doubts because I am actually not that sure. I already know how can the mountains humble one's pride. When then the man helps me with a backpack full of food (I did a lot of shopping in Tbilisi, who knows when I will have the next chance), he just sighs "molodeeets" (a kind of a Russian expression for a comliment meaning "good job") and, honestly smiling, wishes me good luck.

From the balcony of the last house in the last village, an old lady with a granddaughter behold me. I haven´t found any spring in the village so I ask them for water. They invite me to the garden, 10-years old Anja speaks perfect Russian. From an early age, she lives in Georgia, but she was born in Ukraine. Her grandma makes a coffee and so we sit on the terrace and chat. Anja has many questions but also talks a lot about herself. Her grandma doesn´t speak Russian and only smiles, but Anja translates for her from time to time.

"Which mountain are you going to climb now? Saurbe?"

"Saurbe? That´s that one with the rocky top?"

"Yes."

"Yes, that´s where I am going."

"But it´s an awful place. The grass there is as tall as my father. Go some other way, no one goes there."

"Nobody? One more reason to go there"

, and Anja conspiratorially smiles at me, that she understands. When I then thank them for coffee, they invite me to spend a night at their place but I am already drawn like a magnet to the mountains. Anja accompanies me a bit beyond the village and promises to write me.

I start climbing and scorching hot, late afternoon sun tries to suck all the water from my body. I have to think about the last encounter and feel a fondness for both women looking at the world from the opposite perspectives. Suddenly, I hear a sharp swish above. I raise my eyes and I am spellbound - a huge flock of bee-eaters crosses the sky above as if they wanted to completely fill it with their colorfulness. I slump into the grass and watch this symphony of colors till the sun sets down and birds disappear. I am full of joy, this is the first time I saw anything like that.

On the next day, I find out that Anja's father must be really tall. The terrain is terrible. The slopes are steep and overgrown by towering thistles and other unpleasant vegetation. I finish the day by climbing onto the narrow ridge behind Saurbe. Round, salmon-colored moon lights my path (but actually, there is none at all).

On the next morning, I wake up in the middle of a cloud. I can´t navigate the ridge under these conditions so I take a nap till the noon when the fog disperses. But I walk only for a few hours. Grey, heavy clouds rush from the north and while I traverse the ridge (I have only half a liter of water from the evening and unsuccessfully try to find more), the storm comes and thunders deafeningly sound everywhere around. When I finally make it into the small saddle, numb and wet, I build a shelter and look forward to collecting the water from it. I place my mugs at strategic places but just as I crawl into a sleeping bag, the thundershower turns into a drizzle.

The next morning is astounding. I have nothing to drink but don´t want to climb down to look for water. I need to cover some miles since I hiked very little in the past two days. But in the afternoon, I am tormented by thirst and spend more time by resting that by walking. I descend to find some water but all springs are dried up and I have to climb all the way down to the treeline. This "water expedition" costs me three hours. When I in the evening slowly fall asleep at a place with a wonderful view, the clouds ahead disperse and my smile freezes. Ahead, I can see three rocky elevations and beneath them is such a precipice that if I slipped, not much would be left of me at the bottom of the valley. For the next hour, I have a tantrum of indecision. The mountain calls me but I have a feeling that going there, alone and without a harness, would be fooling. If I fall, I will never be able to explain to my mother which I risked so much. Actually, it would be impossible to explain. So I decide that the next day, I will descend into the valley and then climb onto the ridge behind.

But in the morning I find out that the descent is impossible. Few hundred elevation meters beneath the ridge sprawls a steep cliff. Since I studied the ridge ahead for several hours, I think I know the safest route. It shouldn´t be technically difficult and if I am careful, I will be able to pass. And so I go. I focus only on two things - not to make a mistake and film it all. But once I finally overcome the last peake, I feel no relief. There is a fourth peak, which I originally didn´t take into consideration because I thought it´s not the part of the main ridge (now I see it clearly on the photo). And it looks even worse than the ones I just passed. Behind, I can see another three rocky spikes and then a steep drop. Probably on rocks, that would be very dangerous without a rope. So I can´t go ahead and don´t want to go back. And I am worried because descent is always harder. I lie on my back, bask in the sunshine and feel great in spite of my entrapment. It´s weird, but I am completely relaxed.

Then I make a plan. I will descend the southern side of the mountain which is more grassy and then follow the creek to the bottom of the valley. From there, I will continue to the east and eventually should reach the road heading north to Shatili. The hillside is too steep to walk on it so I just slide down. It´s a lot of fun and thanks to the adrenaline rush, I don´t even mind my scratched buttocks. When I slide about five hundred meters down, the grass turns into a jungle of hogweeds, thistles, and nettles - that´s not so much fun anymore. Eventually, I reach the underbrush which is almost impassable and decide that it´s time to descend into the canyon and just follow the trough of the creek. But once I make it to the creek, I find myself at the top of a high waterfall. It´s getting dark and so I, as always when I don´t know what to do, break a camp.

The morning is splendid and I happily plunge myself under the waterfall (I bivouac at the spot between two waterfalls). I am surrounded by a total wilderness, the terrain is close to impassable. I am so happy that I am alone in the middle of nature and like it here so much that I spend here almost the whole day. I never want to get dressed again. I set off only in the late afternoon. The high waterfall beneath me cannot be climbed so I bypass it through the steep slope. On the way down, I encounter many other waterfalls but none of them is as dangerous. It is wonderful, solo canyoning. I pass the most difficult section before dusk and break the camp again. Now I only have to follow the normal creek to the east.

Even though the Gudamakari mountains denied me my planned crossing, they still showed me lots of beauty and some of their secrets. The creek, which I follow towards the main road is full of transparent natural basins, around me stands an ancient, primeval forest. And I am so happy about it that I stop being careful and jump down from one rock so clumsily that in the next moments I kneel on the ground and dampen the pain by exquisite profanities. For almost an hour, I cool my foot in the creek. Then I remove the bandage from my knee, tie the ankle, somehow put that thick foot into the boot and keep walking. Slowly, but steadily. Although the ankle is badly swollen and I can´t sleep during the first night because of the pain, I believe that if I take it easy, the sprained ankle will completely heal in two weeks.

On the next day, I spend the afternoon at the small hospital in Barisakho. Not because of an ankle but since I can recharge my camera batteries here and no one minds. In the evening, I follow the dirt road to the start of the Chaukhi pass trail. I head west, even though I should go in the opposite direction, but I can´t help it, I want to get a closer look at those rocky three-thousanders north of Gudamakari mountains. On the next day, I befriend the children of Roshka. After we deplete their English vocabulary, they start teaching me Georgian so now I know many new, important words such as trees or socks. When then 10-years old Tamara admires my lucky charm which I carry from the Black Sea, I give it to her and head north to the lakes. At the dusk I meet four muscular lads and since they are obviously locals, discuss with them the possibility to cross the Gudamakari mountains from the south. They claim that it´s not possible but I think that it should be doable with some detour and want to try it again when I once return here.

On the next day, I loiter by the glacial lake and soak my ankle, only in the afternoon I head straight up, towards the pass. The trail is terrible, covered with rubble and so I rather climb up the dried trough of some creek. Still not a win. Not far beneath the ridge, I see a woman with a colorful crossbody bag descending towards me so I yell at her in English that she should rather return onto the marked trail. And so we keep yelling for like five minutes until we finally meet. Then she turns to her approaching boyfriend: "Pavel, this girl says that we should return to the blue-marked trail." And so it turns out that they are Czechs, Pav & Mon and that's it, and that they´ve been traveling around the world for the last five years.

"We didn´t have a normal job in the past 18 months", laughs Mon. And we are obviously a perfect match because we just stand in that steep, rocky slope and keep chatting for more than an hour. Pavel seems to be already a bit nervous since he would like to break a camp before the dusk. But we are so excited about our meeting that it´s hard to part our ways, so we settle on meeting two days later in Stepantsminda so we can finish the talking. And I continue over the Chaukhi pass to Juta.

While waiting in Stepantsminda, I make a trip to the Sameba church - the views of the Mt. Kazbek are magnificent and I am a bit sorry that I don´t have a climbing buddy. Once we meet with Mon and Pav again, we chat nonstop till midnight and then bivouac in the nearby forest. In the morning, we want to part our ways - they plan to climb to the glacier, I need to get back to Juta. But we can´t stop talking and I don´t even try because I know that once we say farewell to each other, I will miss them. So we chat till the evening when it´s really about time to say "goodbye". On the same evening, I effortlessly hitchhike to Juta and when we are getting close, the driver points and the mountain above: "That snow is fresh. It fell yesterday." And I realize that until now, my Caucasus adventure was just fun. And that fun will be over soon.

At the border guards camp behind Juta, I get a trekking permit for my planned route. Then I slowly crawl deeper into the beautiful valley and I meet two soldiers on horses. They look so tough that I actually get scared when they talk to me in their deep, growling voices. In the evening, I cross the 3000 meters high Arkhoti pass and bivouac behind. On the next day, I meet likable Zdenek who also likes to wander alone in the mountains and get from him some valuable tips for the Nagorno-Karabakh.

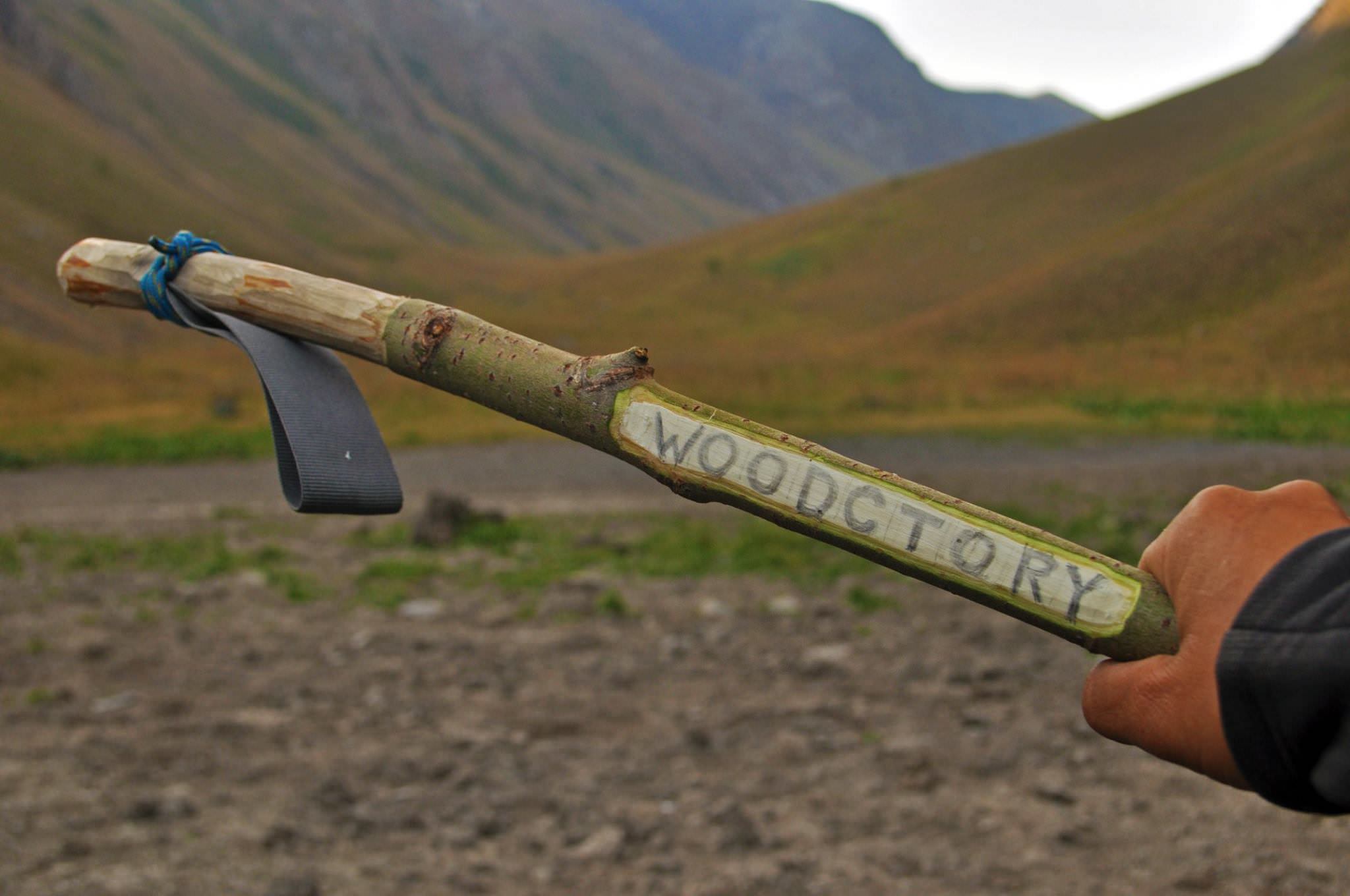

Since my trekking poles were stolen in Stepantsminda, for the last three days, I have to manage without them. But my knees start complaining. So I make new ones from young saplings and cut the material for straps from my hip belt - in past months, I lost some weight so now it is too long for me, anyway.

In the evening, I am stopped by another group of soldiers. While I wait till they check my permit, I get bread and fried eggs. Then they invite me for the dinner, but then I would have to sleep there and I would much rather sleep up by the Tanie lake than to listen to their snoring and farts at the base. On the next morning, I bathe, cook and wash my clothes, it´s the first autumn day. But in the afternoon, the storm chases me out and in the evening I enjoy the views from another 3000m high saddle. On the next day, I gather rosehips. Some sorts taste like pepper, carrot, celery or simply like rosehips and in the evening, I use them to cook a risotto. It´s abnormally delicious.

In the morning, I hitchhike to Barisakho to recharge my camera batteries. While charging, I play with Tekla and Bard but less than an hour later comes the blackout. The neighboring village is without power, too, supposedly till the evening. I go to buy bread and meet a nice group of Czechs and Slovaks who offer me some sweets and beer. In the afternoon, I camp by the river, eat sweets, drink the beer and suddenly feel so tired that I fall asleep and don´t wake up before morning.

On the next day, I visit Arabuli Guesthouse in Korsha where I meet a very kind lady which totally looks like Olga Havel. She lets me recharge batteries and doesn´t complain at all that I spend half of a day on their terrace. Then I follow the main road to Shatili. It rains for the most of the day, at the Datvisjvari pass I get caught by the hailstorm. I bivouac in the huge pipe. I don´t know why, but whenever I sleep in the pipe, I feel completely satisfied...

Behind the Datvisjvari pass, I leave the Shatili road and cross another pass where I find many quartz crystals. Then I follow the Chanchakhi river valley till the evening and climb through some scorched area up, towards Atsunta pass. I bivouac very late, in the dark and fog. In the morning, I am chased from my shelter by a border guard. Maybe it would end differently if he simply said: "I am sorry to bother you, young lady, but I have to check your documents." And maybe it would end differently if I immediately handed him my passport and wasn´t huffy. But I refuse to accept bad manners from some tough guy, especially early in the morning. I think it´s understandable. But he didn´t understand. And lost his nerves. And so, while the snow falls at the Atsunta pass and the soldiers at the nearby camp in the middle of the scorched plain toss the dough for bread while waiting for their superior, between two people, who´ve just met occurs drama so embarrassing that Hana Heger could sing about it, the situation so absurd that even Lars von Trier could get inspired.

I´ve never seen someone so angry. And then, when I think that he will hit me with the rifle butt (in the best scenario), probably the sun shines on my hair or something, but the man suddenly calms down and stops threatening me. So I start packing and he can´t understand that I don´t have a tent, asks me about my equipment and how I trek in the mountains and probably gets impressed because he soon apologizes that he was so rude in the morning and stresses, with the expression of a wounded puppy, that he is sorry. And I suddenly feel very sorry for him and even though I think that he is an idiot, I tell him that nothing happened and everything is OK.

When he then prepares me a permit, which I, of course, didn´t have, (because of the non-standard route, Vicky missed the Mutso checkpoint which issues Atsunta permits - Jozef), I drink tea with other soldiers, we chat and it eventually turns out that two of them are from Korsha and personally know that Georgian Olga Havel. And when their commander hands me my passport and permit, the soldiers ask me to stay a little longer, until they bake that bread. And I would gladly stay because they are nice but then I notice that all four eye me like a holy icon and I realize that it´s time to go.

While I climb, the weather gets worse and worse and at the elevation of 3400m, it snows. And when I descend from the pass into the valley, the rain starts so I hide into the shepherd´s hut and prepare the late lunch. When the autumn comes, the shepherds take their herds into the lowlands. And I can use their abandoned huts as a refuge from the bad weather. It rains till the evening and then the whole next day. After the dark falls, I bivouac beneath the cornice and spend there another whole day - I have sore hips and I am in no mood to walk in the heavy rain. Then the rain ceases and I happily rush down the valley, admiring all that snowed beauty and charming Tush towers, which are even more impressive than those in Svaneti. And sooner than I expected, I see Keselo castle where I did some minor archeological works with my Czech friends two months ago. I made it to Omalo.

Here, the diary ends. During the next month, Vicky hiked to the east, reached Azeri border and eventually also the Caspian sea. Unfortunately, she didn't document this part of her journey, mainly because the trekking in Azerbaijan is pretty regulated and she had to break several rules to get into the mountains. But she promised to write about it, too, so sooner or later, these diaries should get a fitting ending. In the meantime, you can follow her adventures at her personal website (at least if you understand Czech).