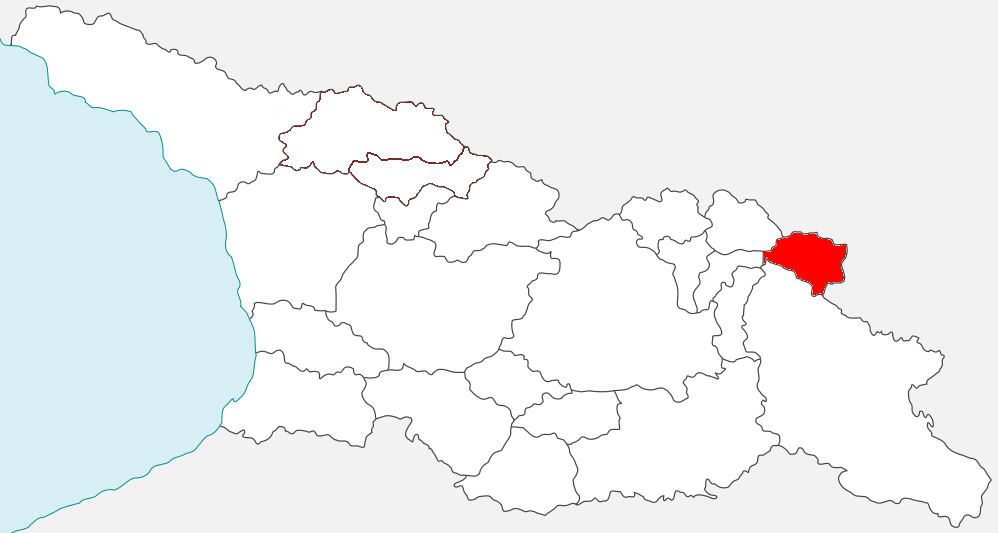

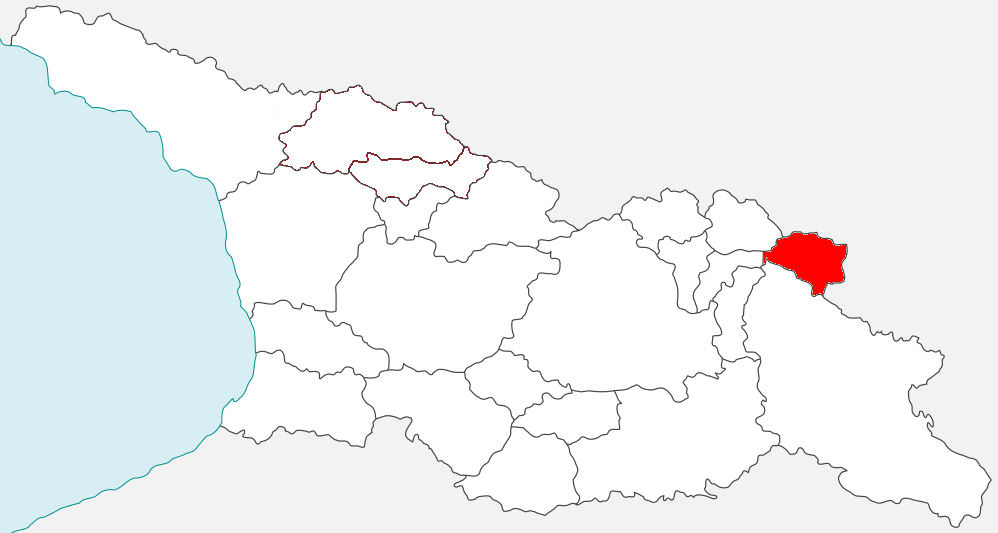

Tusheti

Tusheti is a pristine, remote region tucked in the mountains of northeastern Georgia. Compared to places such as Svaneti, the landscape here is not as dramatic and you won't find many glaciers here. On the other hand, the place has a very unique, exotic atmosphere, reminding some kind of a "sleepy fairyland".

PRACTICAL INFO

- 1. Overview

- 2. Getting around

- 3. When to visit

- 4. Where to stay

- 5. What to eat

- 6. Things to do

- 7. How to behave

UNDERSTAND SVANETI

- 8. Tush people

- 9. History of Tusheti

- 10. Local beliefs

- 11. Important festivals

- 12. Local issues

1. OVERVIEW

Lying deep in the mountains, this is the most isolated region of Georgia - to the north and east stretch closed Chechen-Daghestani borders, to the west, behind the mountains, lie similarly isolated Pshavi and Khevsureti. And from the south is Tusheti bordered by 3000 meters high ridge of the Greater Caucasus. The only lifeline connecting Tusheti with the rest of the country is the treacherous road crossing 2850 meters high Abano pass. It is unpaved and very bumpy - that's also a primary reason why Tusheti is not yet swarmed by tourists. Even though their numbers are steadily rising (from 1000 tourists in 2008 to over 15000 visitors in 2018).

Geographically, Tusheti consists of three main valleys which gave names to the subgroups of Tushs inhabiting them. Pirikiti Tushs inhabit the valley of Pirikiti Alazani, running in parallel with the Russian border. The most important villages in the valley are Dartlo, Parsma, and Girevi. Gometsari Tushs live in the Tushetis Alazani valley, their most important villages being Jvarboseli, Dochu or Verkhovani. Both rivers eventually merge - the nearby area is inhabited by Chaghma Tushs. Here lies Omalo, the center of the whole region as well as other villages such as Shenako, Diklo or Khiso.

There is also a specific area by the Tsovata river, one of the subsidiaries of Tushetis Alazani. This already depopulated valley once housed eight villages of Tsova Tushs (calling themselves Batsbi), a distinct branch of Tushs speaking their own language.

The life in Tusheti is outlined by two main events - the opening and closure of the mountain road. The road to Tusheti usually opens in late May when the bulldozer clears the path and local shepherds herd their flocks of sheep through Abano pass to summer pastures in the mountains. They are followed by tourists and hikers willing to experience this unique area. Also, many Georgians from lowlands travel here to "reconnect" with their ancient homeland. Then in the autumn (usually at the end of September) shepherds drive their flocks back to the lowlands and road soon gets blocked by snow. And Tusheti falls into its winter sleep again - only border guards and a few dozens of people (titled "tushuraebi") stay here during this period to look after abandoned villages.

Shepherds return to Tusheti in the early summer (by Dmitry Gomberg)

2. GETTING AROUND TUSHETI

Getting in

The only road connecting Tusheti with the rest of Georgia crosses 2850m high Abano pass. It was built in the 80s and since then, it saw only necessary maintenance (not counting the sections which must be essentially rebuilt after spring landslides). Because of this, the travel speed here is limited and this 50km long stretch may take even 4 hours to finish. However, the government has recently promised a masisve reconstruction which should greatly reduce travel times.

By jeep:

There is no public transport to Tusheti. To get to Omalo, you will need to hire a driver with 4WD. If you are traveling from Tbilisi, you will first need to get to Kvemo Alvani village - this can be done by marshrutka or a taxi.

The marshrutka departs from Ortachala bus station in Tbilisi at 9.am and arrives at Alvani two hours later (price 20 GEL). Drivers are used to tourists and often arrange them further transport to Tusheti. Just confirm with the driver that he is going all the way to Alvani, they sometimes try to drop passengers in Telavi in order to make them hire another taxi to Alvani. Or they simply want to hook you up with the jeep driver from Telavi but that is OK if the price is right.

If you want to take a taxi from Tbilisi to Alvani instead of a bus, the price can be anywhere 100 and 150 GEL (it grows with your distance from the Ortachala station :))

In Kvemo Alvani, the bus or taxi will drop you at the main (and the only) junction. This is the place from which depart jeeps to Tusheti so if you get here before noon, you should be easily able to hire a driver.

The ride to Omalo takes about 4-5 hours and costs about 100 GEL per passenger (or about 350-400 GEL for the whole jeep). BBC once placed it among the "10 Most Dangerous Roads in the World", but with a good driver, it definitely doesn´t feel like that. In navigates pretty steep mountainside but the road is usually wide enough and unless you are passing another car and need to navigate to the very edge of the road, there is no reason to feel nervous. Still, the accidents happen here and the road claims a few lives every year. Therefore, even if you have your own car, for this stretch of the road, it may be better to use the service of the local driver.

By hitchhiking:

Hitchhiking can be "hit or miss" since jeeps traveling to Omalo are usually booked by tourists and full. And even when they are not, tourists might be reluctant to pick someone who just walked a few hundred meters beyond the departure point and raised a thumb (especially if he is dressed up in Arc´teryx gear like a couple of "travel hackers" we saw there the last time :)). Professional drivers will rarely pick you up for free. Therefore, your best bet will be locals heading to Omalo for a visit - but it may take a while until some show up.

Another option is the Kamaz truck which brings supplies from the lowlands to Omalo. These drivers usually pick up passengers for a symbolic price but the truck has no fixed schedule. It departs like each other day in the morning, so it can´t be relied upon.

Road to Tusheti

Getting around Tusheti

Getting around Tusheti requires some planning. There are roads running at the bottom of three major Tusheti valleys but the traffic is minimal and cars usually full. If you want to reach some more distant villages without walking, you may have to hire a car. Here are the approximate prices for the ride to the most popular destinations.

| Destination | Price |

|---|---|

| Dartlo | 100 GEL |

| Ghele pass (Pirikiti range hike) | 70 GEL |

| Diklo | 70 - 80 GEL |

The only problem is that majority of drivers speak only Georgian or Russian. Therefore, it´s good to have also the number of Tusheti Visitor's Center (+995 577101892), which is located close to the Lower Omalo. The staff there speaks English and wil be able to arrange you a driver if you need one.

Leaving Tusheti

Again, you will have to hire a jeep with a driver or hitchhike - if you are staying at the guesthouse, they will arrange this for you, if you are camping, you need to ask around the village or at the Visitors Center. In this case, it makes no sense to return to Kvemo Alvani, it´s better to ride to Telavi which is a much larger city. The price of the ride is again 50 GEL per passenger.

You can also inquire about a direct transfer to Tbilisi. Jeep drivers probably won´t drive you all the way to the capital but should be able to arrange you another taxi so you can switch cars once you leave the mountains. The total price of such transfer is usually 70 GEL per person.

Tusheti

3. WHEN TO VISIT TUSHETI

Travel to Tusheti is limited by the status of the mountain road linking the region with lowlands. From the autumn till the spring, the road is blocked by snow and therefore unpassable. And even after the snow melts, some sections get damaged by landslides and must be rebuilt. For these reasons, the road gets usually opened in the late May or (like in years 2017-2018) even in the first half of June.

Overall, June is not the best time to visit. Apart from the occasional road closures, you need to be aware of the fact that not all Tushs have already moved into the mountains. That is not such an issue in a larger village such as Omalo but could pose a problem if you reach some more remote hamlet and find out that its only guesthouse has not opened yet. Moreover, June tends to be quite rainy, especially it's first half.

July and August is the high season. All facilities are open and the region gets the largest amount of visitors.

September is also fine - the temperatures during the day are still pleasant while there are not so many tourists around. In the second half of the month, shepherds start moving their herds into the lowlands. In October, one can expect first snowfalls at the higher elevations. The Georgian road department keeps the road open for some time and then, depending on the situation, announces the date when it stops the maintenance (this occurs in the second half of October). The road stays open for the next few days, but sooner or later, another round of serious snowfalls seals it till spring.

In winter, Tusheti is off-limits. There are regular helicopter flights which are used for rotation of border guards or medical emergencies but to get a place you would have to be a soldier, deputy or some other local big shot.

Dartlo in autumn

4. WHERE TO STAY IN TUSHETI

People visiting Tusheti are mostly staying at guesthouses or homestays. There is a wide selection of guesthouses and the list keeps growing but many of them have no online presence, can be booked only by a phone call and owners don´t speak English. Therefore, if you want to visit Tusheti on your own, don´t speak Georgian and Russian and don´t mind having a set schedule, the best option for you may be the using of service of online portals such as booking.com, at least for the first night in Omalo. Here, you can ask your landlords to make other, trickier bookings for you. Below, I provide a short and incomplete list of places with a solid reputation.

Accommodation in Omalo

When booking the accommodation in Omalo, keep in mind that the village actually consists of two parts - Zemo (Upper) and Kvemo (Lower) Omalo. Upper Omalo lies on the hill in close proximity of Keselo fortress, is smaller, more scenic and the prices here are therefore higher. Lower Omalo is larger and offers a wider range of budget accommodation. However, it lies further from the fortress - if you want to visit it, expect at least 15-20 minutes of brisk uphill walking.

Majority of guesthouses use the power provided by solar panels, which means that sometimes they run out of hot water (which is not always in sufficient supply since the village lies on a hill). Pls keep this in mind and don´t spend too much time in the shower.

Hostel Tishe

Tishe is a pleasant hostel located in the Lower Omalo offering superb value for the money. The bed are comfortable and rooms small but clean. We also liked the cooking skills and attitude of Eto and the rest of the staff, though they spoke very little English (might have improved since 2016). At this hostel, you can find also the only shop in the village where you can buy not just food but also fridge magnets, hand-made socks, and other souvenirs.

E-mail: inga.chvritidze@gmail.com

Lasharai Guesthouse

Lasharai is a new, modern guesthouse located at the Upper Omalo (opened only in 2015). Featuring the nice stone interior, English speaking staff and above average prices, its geared towards more demanding tourists. Both breakfast and dinner is delicious and already counted in the price of the room.

Guesthouse Tush Tower

The Tush Tower (or Tushuri Koshki) guesthouse is situated in the Upper Omalo and is one of the very few places offering the sleeping in the authentic Tush tower. This is a very cool experience in both meanings of the word since Tushs didn´t use glass windows :). But the hosts do their best and supply you with enough pillows and blankets to keep you warm.

This place has also one more advantage, which is reflected in the way it looks - it is owned by a well-known Tush ethnographer Nugzar Idoidze. He is a true treasure trove of knowledge when it comes to Tusheti, but doesn´t speak English, only Georgian and Russian.

Tevdore guesthouse

Small, nice guesthouse located in Lower Omalo with a very friendly staff.

E-mail: nkindolauri@gmail.com

Guesthouse Shina

Another nice, modern guesthouse situated in the Upper Omalo. Offers clean, spacious rooms and great food. Also, the staff is very friendly and speaks some English.

E-mail: hotelshina@gmail.com

Keselo guesthouse

Pleasant guesthouse located between Upper and Lower Omalo. Offers good value for money and good food. Also, it is possible to camp in a garden for the symbolic price.

E-mail: guesthousekeselo@gmail.com

Upper Omalo

Accommodation in Dartlo

Guesthouse Shuni

Cozy guesthouse situated in a small stone house, only three rooms for total nine visitors. Run by sisters Salome and Tamro (and their three cats). Pleasant hosts, warm blankets, terrific food - there is nothing not to like;

Facebook page (could be used for booking): Gueshouse Shuni

Samtsikhe guesthouse

Spacious guesthouse located at the bottom part of the village, close to the road. Offers simple but clean rooms, lots of food and also staff which speaks some English. Features also a restaurant in the nearby building.

E-mail: beselanidze@yahoo.com

Accommodation in Girevi

Guesthouse Nadukurta - Small guesthouse in Girevi, the last inhabited village in the Pirikiti Alazani valley. Ruled by caring and energetic Lela. The facilities are a bit basic, but that´s understandable considering the location of the guesthouse. On the positive side, the place is clean, has a good vibe and the food is tasty, plentiful and relatively cheap..

Accommodation in Gogrulta

Lily's guesthouse - Small homestay in a remote village Gogrulta, spectacularly located on the cliff above Tushetis Alazani valley. Operated by a pleasant elderly couple - neither Lily nor Sokrat speak English but during the summer, they usually have grandchildren around which could be used as interpreters.Phone: +995 595 143 487

Accommodation in Verkhovani

Lamata guesthouse - A small guesthouse located in Verkhovani, the last inhabited village in Tushetis Alazani valley, operated by the only family living there. Anzor and his family are nice hosts, even though they don´t speak English. They rent rooms in the old Tush tower which are quite spartan but considering the remoteness of the village, one has to be content with what is provided :)Phone: +995 599 700 378

Spartan accommodation at the Lamata guesthouse

5. WHAT TO EAT

Until recently, the only way to get some real, warm food was at the local homestays. It´s no longer the case but I still think that eating at homestays is overall the better option - the food there is generally tasty, plentiful and for a good price. Almost all guesthouses offer breakfasts and dinner and sometimes even calculate it in the price of the room (better ask in advance).

The good thing is that you can often arrange a breakfast a dinner even if you don´t stay with them - so, even if you plan to camp, it is a good idea to arrange a feast through the local homestay. They should be notified at least one day in advance so they have time to prepare.

Nowadays, you can visit also a couple of restaurants. There are at least two in the Upper Omalo (Dariani Wine Bar and Cafe Khavitsi) - both focus on drinks but offer also some food) and one in Dartlo village (Samtsikhe restaurant). These places are still family-owned and offer a good level of service.

Tush cuisine

People of Tusheti are traditionally shepherds and their cuisine is based on meat and dairy products. Overall, it doesn´t differ too much from traditional Georgian cuisine. Also in Tusheti, we can find khinkali and khachapuri (here it is thinner, filled with cheese or curd and called kotori). Traditional shepherds meal is khavitsi, a high-calorie mix of salty curd and butter. But the most famous local product is "guda cheese", tasty sheep cheese which ages in sheepskins.Tusheti is also probably the only Georgian region which has a long tradition of brewing beer. For the centuries, they´ve been brewing aludi - sweet dark beer made of hops and mountain barley. Originally it used to be consumed only during local festivals but nowadays is available all summer long.

6. WHAT TO DO

Trekking and hiking

I assume you this is not new to you since you are on this web, but Tusheti is a great hiking destination. It offers a wide range of trails of varying length and difficulty. Even if you don't have a tent, there are several nice day hikes you can do around Omalo or, even better, you can hike between villages. The largest such loop you can do around Tusheti takes 5 to 6 days to finish.Many more options open up if you have camping gear. Two trekking trails head west into the neighboring Khevsureti - the more popular one crosses 3431 meters high Atsunta pass, the other lies further to the south and uses 2900 meters high Borbalo pass. Two other little-visited trails head south into the Pankisi Gorge, using Sakorne or Samkinvrostsveri pass. An extensive and yet desperately incomplete list of available treks is available on a separate tab of this post.

Mountains of Tusheti

Horse-riding

Tusheti is a premium horse-riding destination. The most usual trails follow the dirt roads at the bottom of the valleys. The center for this activity is Omalo - there are about a dozen locals offering their horses for hire. The usual price for a horse is 40-50 GEL per day plus you will need to hire one guide which costs another 50-70 GEL.

Mountain biking

Tusheti also offers opportunities for biking. One of the popular rides lies on the road to Tusheti - it is downhill from 2900m high Abano pass. Here, you will lose more than 1300 meters of elevation during the 25 km long ride. Just be wary of the passing jeeps.Many other trails lie inside the park. Tusheti has many dirt trails and tracks used by shepherds which see little car traffic and are therefore very suitable for mountain bikes. More technical riders tend to traverse the Pirikita range and finish with an adrenaline descent from Nakle-Kholi pass to Parsma.

Each year, there are also several bikepackers who cross Atsunta pass to Shatili (tho I heard that bikers prefer doing it in the opposite direction).

Mountain biking in Tusheti

7. HOW TO BEHAVE

Respect shrines and holy places

While wandering around Tusheti, you will probably see small stone shrines, often adorned by bells and animal horns. These so-called "khatebi" ("icons") or salotsavi ("holy places") serve as a place of prayers, sacrifices, and other religious rituals. Because of Tushetian dualistic understanding of the world, there are two opposing cosmic principles, represented either by a woman or a man. At some occasions, these principles interact, but holy places must stay "clean" - the presence of opposite force would defile them and bring chaos (more in the section about Tush beliefs ).In Tusheti, almost all outdoor shrines are dedicated to the principle represented by men and women, therefore, shouldn´t approach them. Technically, this limitation applies only to women which still have a menstrual cycle, but I would recommend avoiding these shrines even if you are an older woman -you certainly don´t want to play the game of charades with angry locals, demonstrating the word "menopause".

Leave bacon in the lowlands

Tush people consider pork meat to be unclean, don´t consume it while in mountains and don´t use pork products such as leather. The origin of this custom is unclear but could be a result of the influence of neighboring Muslim tribes. Another reason might be that herding pig in the mountains was more difficult and has more hygienical risks. Either way, locals believe that taking pork in Tusheti brings chaos and misfortune.Interestingly, this applies only to the consumption of pork in Tusheti, which is considered to be a place of purity. While in lowlands, Tushetians eat pork without any issues.

Don´t ride the horse in the village

In Tusheti, strangers shouldn´t ride the horse in the village - this custom originates in the past when the region was subjected to pillaging raids. Therefore, it´s a sign of good manners to dismount before you enter the village.8. TUSH PEOPLE

The origin of Tush people is not completely clear. According to some sources they are genetically Georgians, other theory claims that they are descendants of Nakh people of the northern Caucasus. According to others, Tushs are people of mixed ethnic origin - this makes sense since over most of its history, this region had served as a refuge for people looking for religious asylum. First for Pshav and Khevsur pagans fleeing Christianization, later for Ingush Christians which tried to avoid coercion to Islam. That could also explain the fact that in this pretty small area, two distinct subgroups emerged. Besides dominant Chaghma Tushs, which speak Tush dialect of Georgian lived in Tusheti also Tsova Tushs (or so-called Batsbi) which used the language rooted in Nakh dialects of Northern Caucasus.

Despite the different language, both communities peacefully coexisted for centuries, identifying themselves as Georgians. Then, in the first half of the 19th century, Batsbi Tushs abandoned their mountain villages and resettled to the Georgian lowlands. Up to these days they live around Zemo Alvani village, being slowly assimilated into the Georgian majority. Their language (batsbur mot), being fluently spoken only by a few dozens of elders is on the verge of extinction. More info can be found on this nice web about the Batsbi people.

Tush shepherds

9. HISTORY OF TUSHETI

Ethnologist keep arguing about the origin of Tush people, but we may never find the truth. Archeological findings suggest that the region was already inhabited during the Bronze Age (2000 BC). Tush people were first mentioned in 2nd century BC by Greek geographer Ptolemy, who placed them next to the Didos, the tribe from Daghestan (Touskoi and Didouroi). Tusheti was at this period probably part of Iber-Kartli kingdom founded by king Pharvanaz.

The first influx of refugees into Tusheti is documented in the "Life of Kartli", the oldest Georgian chronicle. It reports that after Georgia accepted Christianity as a state religion in 337 AD, numerous highlanders from Khevsureti and Pshavi resettled to more remote Tusheti so they could preserve their pagan faith. As a result, we have villages with the same name in both Tusheti and original region (Khakhabo, Omalo), which causes confusion even today. For the same reason, in Tusheti can be found village shrines devoted to Khevsur celestials such as Kopala or Lashara.

People of Tusheti were finally forcefully Christianized in 9th century AD when Tusheti got under the control of Pankisi nobles. However, they kept their pre-Christian religious practices and merged them with the new faith.

At the end of the 13th century, Tusheti was severely hit by Mongol armies led by Tamerlane. During these raids was for the first (and last) time conquered and razed Keselo castle at the Upper Omalo. These events also accelerated the building of defense towers.

At this period, the rhythm of life in Tusheti was defined by the usage of winter and summer houses. During the summer, Tushs used to live in the fortified villages situated as high as possible, where they were safer from the invaders, mostly coming from Chechnya or Daghestan. And during the winter, when the mountain passes were blocked by snow, they descended to their lower winter homes to live closer to their livestock. Nice example by these villages featuring both winter and summer homes are Upper/Lower Omalo or Kvavlo fortress above Dartlo.

Shepherding in Tusheti

Conflicts with their northern neighbors presented a constant threat. Almost every major tower in Tusheti has a legend about some siege, battle or skirmish in which it played a crucial part. But I would like to stress that these relationships were reciprocal, it wasn´t like that Tush tended to themselves and Chechen kept attacking them. Tushs also raided villages to the north in search of cattle and women. And the relationships were not always hostile, Tushs and Leks/Nakhs (the older names for the tribes to the north) often traded and, paradoxically, many Tush defensive towers were built by Dagestani masons.

From the 16th century, Tush gained the right to use winter pastures in the Caucasian foothills, particularly in the Alazani valley. In return, they pledged to pay taxes and provide military support to the Georgian kings. Then, in 1659, they got these lands by royal decree. It was a reward for their support of Bakhtrionhi uprising, a revolt of Georgian nobles against Persians which planned to deport Kakhetian peasants and colonize the whole region by Turcoman tribes (see Zezvaoba festival). From this time, a center of Tush economic activity slowly moved to the lowlands. This culminated in the first half of the 19th century when the whole population of Tsova-Tushs permanently resettled to the area around Zemo Alvani.

Abandoned village

During the 18th century, the frequency of raids from the Dagestan greatly increased. Tushs had to repel the attacks of northern tribes which, under the pressure from Russia, tried to link their holdings with the Ottoman empire to the south. Therefore, it was no surprise that when the region got engulfed in Great Caucasian War (the uprising of Caucasian tribes led by Imam Shamil in 1840-1859), Tushs supported tzarist Russia and many served as auxiliaries in its army. During this period, several Tush villages were repeatedly attacked and in some cases even razed, especially Shenako and Diklo. After the defeat of Caucasian Imamate, the raids from Dagestan almost ceased and got reduced to occasional thefts of cattle.

In the 19th century, the majority of Tushs were already moving between summer pastures in Tusheti and winter bases around Alvani village. This gradual movement to the plains was accelerated during the Soviet rule, first peacefully, but after the Second World War were Tushs deported to lowlands by force. Villages in the mountains were marked as "not perspective" and had to be gradually abandoned. Tush shepherds still spent summers in the region, but only as workers at Soviet "kolkhozes".

The Georgian government has decided to resettle Tusheti during the seventies. It allowed people to return, rebuilt the original track into a car road, built power lines from the lowlands (their remains can still be seen along the road) and in Omalo opened facilities such as library, kindergarten or health center.

Tusheti in 70-ties

But then came the dissolution of the Soviet Union which hit Tusheti particularly hard. Subsidies which the region was getting were canceled and prices of wool, the main source of income of local people dropped almost to zero. Later, a war broke out in the neighboring Chechnya.

Only during the last 15 years, we register the initiatives to restore the architectural and cultural heritage of Tusheti and develop it as a tourist destination. Keselo foundation, founded in 2003, restored several towers at the Upper Omalo, demolished during Second World War. The same year, Georgian government established Tusheti National Park and in 2010, a large visitors center was opened in Lower Omalo. There are also several initiatives by Czech agencies which provide solar panels to locals or mark hiking trails. As a result, the number of visitors is steadily growing. While ten years ago, less than 1000 tourists visited Tusheti, in 2018 got the region over 15 000 visitors.

10. LOCAL BELIEFS

Tush religion is an interesting mix of local paganism, Christianity with some elements of Islam and beliefs of the tribes of the northern Caucasus. According to the Tush beliefs, there is one God (ymerti) which is incorporeal and never manifests himself. One God has several children, named "chvtishvili", which have human attributes and fight with demons (devi) for the control over the Earth. These may appear to designed people at a specific occasion. Originally, chvtishvili were represented by mythological heroes such as Kopala or Karate, but after the introduction of Christianity was this pantheon expanded by Jesus Christ, St. Mary, various Christian saints and even later by some Georgian kings such as Queen Tamar or her son Lasha Giorgi. In Tusheti, each village had at least one shrine (khati), dedicated to a selected chvtishvili, their patron.

In Tush mythology is present a very strong accent on dualism and the balance of opposite principles, which form the world. One of them, which represents heavens, rationality, purity or consciousness is symbolized by men. The opposite principle represents hell, emotionality, impurity, subconsciousness.. and women. These two principles must be kept in balance to prevent Chaos. This is the reason why the roles of men and women in Tush society are strictly separated - they have different responsibilities in the household and sit separately at the festivals. The blood of women, especially menstrual, is considered to be a strong source of impurity and women, therefore, aren´t allowed to approach the holy places.

Oath stones in Dartlo, traditional place of judgement

This separation is quite paradoxical since the survival of the community depends on the cooperation of both principles. Therefore, it´s no surprise that there were occasions where both principles met and interacted, for example during the agricultural works. Also, there are several games during Tush festivals where the boys and girls competed and "fought". However, I don´t want to get into too much detail here. This area is not yet completely understood and furthermore, I am not an expert and don´t want to distort or misinterpret something as sensible as beliefs. So, let me just shortly describe some of the most important Tush festivals.

Tush khati

11. IMPORTANT FESTIVALS

Zezvaoba

Zezvaoba is the annual festival held in villages Kvemi and Zemo Alvani every last May Sunday. Its purpose is to commemorate Zezva Gaprindauli, who led the detachment of Tush warrior sent to assist Georgian nobles and played a great role in the victorious battle at the Bakhtrioni fortress. It is popular not only amongst Tushs but also among Pshavs, Khevs, and Kists from Pankisi gorge.

According to the legend, Georgian nobles asked Zezva what kind of reward he wanted and he asked for winter pastures for his people. So they decided to give them as much land as will Zezva and his horse, Saghiri, encircled in a gallop. Departing from Bakhtrioni, Saghiri galloped all the way to Takhtis Bogiri (near the Laliskuri village), where he fell and died. At the place of his death was built a shrine - even these days, it is visited by Tushs and Khevsurs who pray for good health for their horses.

Zezvaoba is essentially a typical festival with various cultural events, competitions and market stalls. What sets it apart is doghi - special horse race held to commemorate Zezva Gaprindauli. The doghi starts with a ritual blessing of riders and their horses - they both partake in a symbolic funeral feast, eat, drink and pronounce funerary toasts. At the end of the ritual, the horses are decorated by white cloths - only these horses can take part in the race.

The race starts in Takhtis Bogiri and ends in Kvemo Alvani - it is therefore 4 kilometers long. Some ten years, it was often won by Kist riders which is not taken very well by the audience - for this reason, the festival was sometimes ironically called "zhezhvaoba", which means beating in Georgian. Nowadays, Kists usually don't compete.

Atnigenoba

Atnigenoba is the most important Tush festival. It is held 100 days after the Easter and usually marks the beginning of autumn works such as mowing and collection of harvest. Festival occurs during two weeks, each village choosing a date which suits them based on the traditions and decision of elders. The main organizer of Atnigenoba is so-called Shulta, elected by the village for the next year. Shulta is responsible for the brewing of the festival beer, animal sacrifice and all arrangements related to the feast (but he doesn´t pay it from his own pocket, food is provided by the whole village).

The spiritual side of the festival is handled by Khelosani, "a servant of the cross". Only he has the right to bring out the cross banner out of the shrine and initiate Atnigenoba by a ringing of the bell. Till the early 20th century, khelosani were usually coming from the neighboring Khevsureti.

Then starts the feast, where women and men sit separately. During the festivals, there are also several other other events such as horse race or korbeghela - the ancient ritual dance featuring the rotating human pyramid, accompanied by the singing of centuries-old songs. Another popular event is "chataraoba" - ceremonial (and mischievous) game involving a battle between men and women, often involving kidnapping and ransoms. Some of these traditions can be seen in this old video.

12. LOCAL ISSUES

Tourism

As everywhere else, growing tourism in Tusheti is a double-edged sword. The access to the region is somewhat limited by the bad road and long travel time, yet the number of tourists steadily grows. While less than 1000 people visited Tusheti in 2008, nowadays, their number exceeds 15 000 visitors.

At first sight, it´s not that much. After all, all these people come only for a few days while Tusheti once permanently housed more than 5000 inhabitants. The problem is that tourists have a much higher impact than the people in the past, especially when it comes to water consumption. A growing number of guesthouses have to cater to the needs of the tourists which are used to daily showers, laundry service and so on. Tusheti as a region has a lot of water but Omalo, its main population center, lies on the hill and is dependent on the water from the surrounding hills, which is not sufficient. Therefore, water shortages may occur during the high season.

Another issue is waste management. Tusheti has no facilities to process garbage (not that anyone wishes for a waste incinerator plants here, it´s a National park, after all), but has to deal with its growing quantities, mostly related to tourists. First garbage trucks were bought in 2017 but the system of its collection was not yet implemented, especially in more remote villages. Therefore, locals often dump it in the nearby ditch or even river.

National Park Administration is currently considering entry fees which would help to cover costs related to issues outlined above. But fees or no fees, there are still things you can do - just knowing that these issues exist and adjusting your behavior can help a lot. For the beginning, don´t take long showers and try to survive a few days without the laundry service. Also, if you bring some garbage, especially plastic, don´t toss it away at the guesthouse hoping that the locals with handle it in the environmentally friendly way - instead, pack it and take it with you to the lowlands.

"High Mountain Road" project

Over the past few years, the population of Tusheti was split over the issue of the planned new car road which was supposed to link the region with neighboring Khevsureti (by the Borbalo pass) and Pankisi gorge (here, a tunnel was planned). Lauded by some as "a great piece of development, which will open remote areas also to children and elderly" and by others marked as "an environmental and cultural disaster", it was meant to open Tusheti to the mass tourism.

There are two main problems with the road. The first is, that no one really knows how many tourists can Tusheti National Park handle without serious deterioration of the environment - according to some, current 15 - 20 000 yearly is the upper limit. But with a new tunnel, this number could easily multiply in a year which would have serious consequences.

The second problem is the other branch of the road which was supposed to connect Tusheti with Khevsureti. Here, it would be necessary to build 60km of the road through the mountains of the National Park which were so far inaccessible to the car traffic. You can imagine what it would mean to the environment.

Tush people are currently split over the issue. The project is supported mostly by Tsova Tushs, because the road would pass their valley, currently inaccessible by cars. Tsova Tush moved to the lowlands 200 years ago, but this would help them to return to their ancient homeland and develop tourism there. On the other hand, Chaghma Tushs, which live around Omalo mostly refuse the project. They are worried that the influx of people would damage ecotourism potential of the park and turn a unique destination into a "one night stop at the drive-through of the Caucasus". Also, their home village Kvemo Alvani currently serves as a gateway to Tusheti, there are several guesthouses and many locals make money driving tourists over the Abano pass. But, with a new tunnel, this source of income would be gone.

In February 2019, the government has decided to cancel the Tusheti part of the project. Instead, they plan to renovate existing roads, the one leading to Tsovata being among them - which is a sound compromise and exactly what the critics of the road proposed. So let´s hope they will stick to it - the actual situation can be found in this facebook group of activists opposing the construction.

Shenako village

Thank you for reading all the way down here, I know it wasn't easy :). If you think I overlooked something important or made some other mistake, please let me know. And if you enjoyed it and are into trekking, hiking or Caucasus, you can name your firstborn share it or like my Fb page. Or subscribe to the newsletter.

Also, because of the depth of this post, I have to base it not only on my experience but also on many other sources. The most prominent of them was Czech website about Tusheti, founded by Slavomír Horák, the man behind Tusheti Help Camps and great Tusheti enthusiast. Of the books, the most useful was Being a State and States of Being in Highland Georgia, written by Florian Muhlfried. Several great photos were also provided by Martin Boettcher

Upper Omalo

Towers of Upper (Zemo) Omalo situated on Keselo hill are a sight none of the visitors of Tusheti can miss. They appear in the distance soon after you climb from Alazani valley

and its truly a magnificient sight.

They were built during Mongol invasion in 13th century - originally, there were 13 of them. They offered protection from Mongolian and later Daghestani invaders.

Towers were abandoned in 19th after Russia took firm control of the area, fell into disrepair and were eventually destroyed by Red Army during 2nd World War. The official reason was the posibility

that they could be captured and used by the German army, but it's mostly believed that it was one of the ways the Soviet used to break the independent spirit of mountain nations.

During the last 15 years, seven towers were reconstructed with the help of Keselo Foundation. In one of the towers is nowadays nice ethnographic museum

(or at least should be, I haven't noticed it when I was there).

Towers of Upper Omalo

Castle of Love

Halfway between Omalo and Shenako lies lonely tower called “Castle of Love”, which is connected with local variation of legend of Romeo and Juliet.

Since 2011 is tower accesible via Trail no. 12 from Visitors centre.

"The Castle" offers nice view of Alazani valley between Omalo and Shenako and it's an interesting daywalk in the proximity of Omalo

Legend of the Castle of Love

At the end of 18th century lived in Shenako and Diklo boy and a girl. They really loved each other, but their families didnt support their love.

After they ignored the warnings of elders, they were both expelled from their villages. Nobody was allowed to help them,

but still they built a tower on poorly accesible crag over the Pirikiti Alazani valley. They grew crops and hunted in the forests.

In the beginning they lacked fire, but later one granma from Shenako brought it to them - after villagers found out, they expelled granny too.

Since then they lived there and had four brave sons. Then, one summer Daghestanis came, burned Shenako and Diklo to the ground and killed all men from these villages.

Only four sons from Castle of Love stayed alive. They managed to defeat the army of invaders and returned to Shenako and Diklo.

Here they founded new lineages and today villages can be considered their descendants. Tower was left forgotten apart from occasional visitors.

Castle of love

Dartlo

Dartlo village lies in Alazani valley some 10 km upstream from Omalo. I think its the most beautiful village in Tusheti, mostly because of its uniform architecture -

while in Omalo you can already find many houses with modern roofs, Dartlo with its stone-slated roofs still maintains its historic, medieval image.

In fact, stone houses of Dartlo are not as old as they seem to be - they mostly originate from 19th century. In the village you can find also several defensive towers,

ruined church and “court stones”, where in the past local elders discussed the fate of community and solved disputes. In the hillside some 200m above the village lies

also great tower Kvavlo, which in the past served as refuge from the invaders from Daghestan.

Dartlo village

Alaverdi cathedral

Alaverdi cathedral doesn´t lie in Tusheti but all taxis bound for the region pass it so I guess I could spend a few words about it. It´s visible from afar - a lonely, elegant structure towering above fertile farmlands. And also fortified - it´s obvious that whoever lived here, wasn´t going to turn the other cheek. For many years, it was the tallest religious structure in Georgia (only recently surpassed by newly built Tsminda Sameba in Tbilisi). Summarized and underlined, it is a prime example of medieval Georgian architecture. That's also a reason why the Georgian government submitted it as a candidate for the UNESCO heritage list.

The Place is definitely worth a short visit. Walk the monastery grounds with vineyards and beehives, admire the cathedral from different angles. The interior is not too decorated and many remaining frescoes are in a bad condition (the restoration work is still going on).

During the walk, you will notice dozens of qvevri vessels - monks used to produce a lot of wine since " wine heals soul and flesh, gives strength to thank Creator and brightens your mood". This tradition was interrupted but in 2016 was the production restored and local wine is now branded as Since 1011. Monks run also wine tours (need to be booked in advance).

From Omalo to Shatili

Amazing 5-day trek connecting villages Omalo and Shatili, historical centers of regions Tusheti and Khevsureti - both are still quite unspoiled due to poor roads. Its intriguing not only by natural sights, but also by traditional middle-age villages dominated by stone towers

- Duration: 5 days

- Difficulty: Hard

Trek from Tusheti to Pankisi by Samkinvrostsveri pass

A spectacular 5-day route crossing the mountains into the adjacent Pankisi gorge. Explores rarely visited villages, crosses two mountain passes and offers wonderful sense of remoteness.

- Duration: 5 Days

- Difficulty: Hard

Trek from Tusheti to Kakheti

Little-known shepherds route connecting Tusheti highlands with Kakheti plains that passes along some of the most panoramic ridges in the region. In good weather, you will be rewarded with great views of Tusheti, Dagestan, and Chechnya.

- Duration: 4-5 days

- Difficulty: Hard

From Ghele to Parsma

Hike from Ghele meadow to Parsma is one of the most spectacular day hikes in Tusheti. It navigates Pirikita range, which separates valleys of Pirikiti and Gometsari Alazani.

- Duration: 1 Day

- Difficulty: Hard

Hike to Oreti lake

This walk takes you to Oreti lake, nestled in the mountain slopes south of Omalo. From the lake, you will have great panoramic views of whole Tusheti.

- Duration: 1 Day

- Difficulty: Hard

From Tusheti to Khevsureti through Borbalo pass

The ideal pick for hikers who want to cross from Tusheti to Khevsureti and look for something more difficult and remote than Atsunta trail.

- Duration: 5 Days

- Difficulty: Hard

Trekking in the Larovani and Tsovata gorge

This spectacular, almost unknown route explores some of the remotest valleys in Tusheti.

- Duration: 2 Days

- Difficulty: Moderate

From Pankisi to Tusheti by Sakorno pass

This remote trail follows the old shepherd's route connecting Pankisi gorge with Tusheti.

- Duration: 3-5 Days

- Difficulty: Moderate

From Omalo to Jvarboseli village

This nice trek allows you to explore less frequented parts of Tusheti. It crosses mountains forming the southern side of the valley of Tushetis Alazani river and passes several traditional Tush villages.

- Duration: 2 Days

- Difficulty: Moderate

From Omalo to Diklo fortress

Nice walk from Kvemo (Lower) Omalo to ruins of fortified Diklo village with nice view in all directions. Passes through beautiful, rustic Shenako village.

- Duration: 1 Day

- Difficulty: Moderate

Exploring the valleys of Tusheti

This nice 3-day trail explores Pirikiti and Gometsara valleys of Tusheti region. It combines visits of traditional Tush villages with some serious trekking over Pirikita range

- Duration: 3 Days

- Difficulty: Moderate